We care about your privacy. We attempt to limit our use of cookies to those that help improve our site. By continuing to use this site, you agree to the use of cookies. To learn more about cookies see our Privacy Policy.

Ari Heckman is Rediscovering American Cities with ASH NYC’s Boutique Hotels

Transforming a historic building, a church, and a strip club into stunning hotels.

When Ari Heckman started ASH NYC in 2008 primarily as a design firm, the hotel industry was going through rapid changes. The economy was struggling, generations of people were becoming more savvy and culturally aware, and hotels had to figure out how to create the kind of spaces that could garner appeal in a changing landscape. The boutique boom came in the ensuing decade, making a mark on major metropolises like New York and Los Angeles. Heckman’s passion for design and real estate would lead him to hotels as well, but he began to seek out less crowded markets, where transformative design could change the perception of an entire city. Since then ASH has developed three boutique hotels in three cities, each one completely esoteric and without parallel. ASH has been at the forefront of a new movement towards second tier markets—hotels that will change your experience of a place like Providence or Detroit. Heckman’s approach to design has been the driving force behind one of the most exciting new hotel developers in the industry, so we took some time to speak to him and get his take on the bottomless well that is hotel design.

Tell me a little about your background, when did you get interested in design?

My grandfather was an architect and my mom was an interior designer. And so I always had familiarity with what it meant to build things. As a high schooler I was always interested in cities and urban planning, and I had the opportunity to work for the mayor of Providence when I was in high school so I saw how big civic and public works projects come together.

My grandfather had always given me the good advice to not be an architect or designer in the traditional sense, because ultimately the client, whether its the homeowner, developer, whatever is the one that makes the final decisions. So I internalized that advice, and I was like I don’t want to be a service provider, I want to be the decision maker.

Before ASH began you were working in real estate. How did you make that transition into hospitality?

It was a little bit challenging when I graduated college and was in the work world because really life tries to make you pick a lane. Are you designer? Are you a developer? Are you a finance person? And so I had jobs that borrowed on some of those experiences, but not really well rounded. Then in 2008 I started my own thing, which at that time it was all very informal, I didn’t really know what I was doing. I just knew that I wanted to do something that was an amalgam of design and real estate development, and basically giving design pride of place in the real estate development process because often it is an afterthought, and in my mind it was always really intrinsic to creating long term value. I think value comes from having superlative design, and creating unique experiences for your customer. I didn’t realize it at first, I didn’t have any ambition to be in the hotel business until I sort of stumbled into it, but I quickly realized that it was the truest way of expressing what I’m interested in.

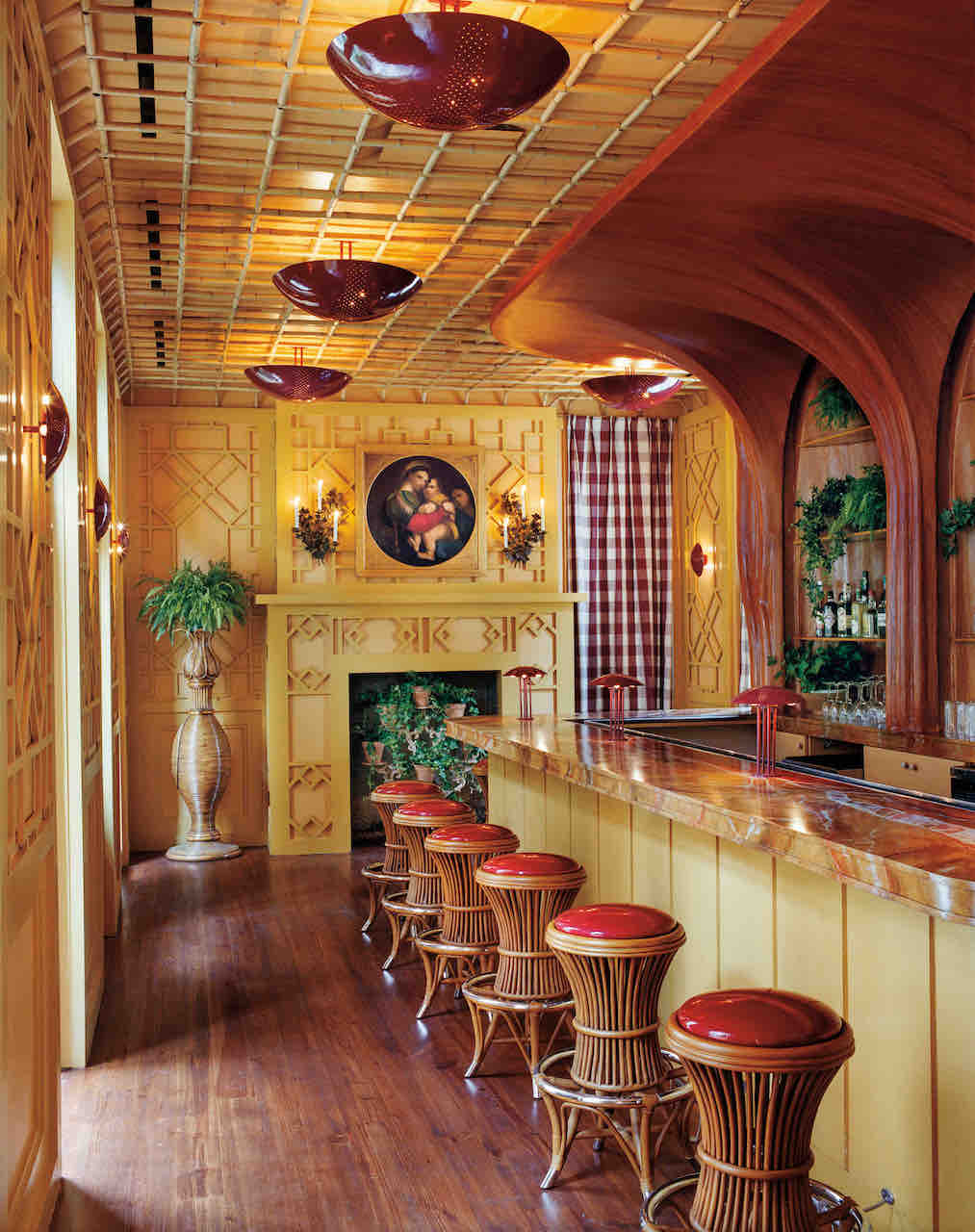

[The Siren Hotel, photo courtesy of Christian Harder]

Did you feel that something was lacking in the hotel industry at the time?

Well, I think I always knew hotels that really appealed to me or the types of places I would yearn to stay, and I’m the type of traveler who part of my choosing where to go is probably based on the hotel that’s there. I wouldn’t say that I necessarily think that something is lacking industry-wide because there are so many different types of hotels and experiences, but I will say that…I like thinking about hotels like people used to think about them in the early 1900’s, where they were like your home away from home; they were super important community anchors. Almost like an embassy where you would go for news and gossip, affairs and indiscretions, all these kinds of cool crazy things that would happen were different than what you would be doing in your home life. The idea of that escape and that fantasy. For me that’s what was exciting about hotels.

Why have you chosen smaller cities as the locations for your hotels?

One of the very basic levels of thinking was like let’s do these projects where they don’t currently exist. I’ve always said I’m hesitant to build a hotel where there’s already an excellent hotel that I would want to stay in. What are places that don’t have good hotels, but the places need to have the DNA of the city that we think is attractive for our type of hotel. Those criteria are interesting, cultural, culinary scenes, historic architecture, basically just cool things happening. I always felt, not necessarily catalyzed by us but concurrent with what we’re doing, this sort of re-discovery of American cities and realizing there is a world of interesting things happening outside of New York and L.A .

I think that hopefully our hotels provide and excuse and launching pad for people who wouldn’t normally go to those places to check them out because I think that some of the best little travel or vacations that I’ve done have been to places that are super unexpected where I’ve discovered really cool things.

[The Siren Hotel, photo courtesy of Christian Harder]

The Dean used to be a strip club, The Siren is a historic building, and Hotel Peter & Paul was a church. What makes you drawn to these existing structures?

From a civic and city building standpoint all of the hotel projects we’ve done have been really underutilized or noxiously utilized and they were all at risk of imminent demolition. That’s one of the really gratifying things, you’re not only like preserving and saving these important buildings, but you’re creating something that’s hugely additive to the host community, you’re creating hundreds and hundreds of jobs, millions of dollars a year of economic impact, and you’re taking something that was blighted yesterday and turning it into a point of pride for the entire neighborhood or city tomorrow. I think one of the cool things for guests who are coming to these places are kind of connecting the dots from their past life to the present. And you don’t get that if you stay in a new box somewhere.

Detroit has gone through a lot of turbulence in our lifetime, what made you feel it was the right time to open The Siren there?

It was a little bit happenstance. I had a few people who were in my life who I trusted and respected their opinions that kept telling me I should go check it out and I always wanted to go there as a student of cities, sort of the great American tragedy, how did we let this powerful city get to this point that it was brought so low, I was expecting so much doom and gloom and ruinpoir. I must have just gone at the perfect time because all of that still existed but I saw the very early green shoots of progress happening there. At that point the entire city government was pretty much shut down so people didn’t need to pull permits for things, it was the Wild West. It felt to me like something was happening there.

That one day I saw this abandoned skyscraper downtown, the Wurlitzer building, and it had a little residential sized for sale sign on it, which is ridiculous hanging on a 14-story building. We ended up buying this building; a lot of people had assumed that there was no way to save it, that it would need to come down, and that wasn’t really the case.

If you haven’t been to Detroit recently it’s definitely worth a visit because what’s happened there in the last five years is pretty astounding. I’ve never seen it anywhere else I’ve spent time; it’s gone from feeling almost completely devoid of activity to being like a cooler Willamsburg now.

The design of the Siren also evokes an older version of the city, perhaps to capture its former glory…

We did a bunch of research on what Detroit was like in the teens and twenties and it was like, they called it the Paris of the midwest, it was this extremely cosmopolitan, polished, elegant city that had these grand old hotels with ballrooms and people had to wear gloves…we wanted to create and recapture that romance that existed.

[The Siren Hotel, photo courtesy of Christian Harder]

How did that vary from the design aesthetic for the Hotel Peter & Paul?

Everything we do is really site specific I would say so we were paying homage to the fact that it was this ecclesiastical property so there’s influence from that. We shopped in Europe for that hotel, we were buying vintage furniture from Italy and the south of France and shipping it home. New Orleans is this kind of cultural melting pot so it was very easy to pull influences from all over the place. Because it’s four different buildings, we sort of challenged ourselves to give a little bit of a different vibe to each of the building so they have their own personality and story.

I’ve noticed that many people refer to the European idea of hospitality, whether it’s in design or in service. What do you think defines the American idea of hospitality?

It’s probably changing and they’re moving closer to one another than they used to be. Certainly I have always taken my inspiration from the European hotel experience, a little quirky a little less conventional, more willing to bend the rules and not play by a certain format. I don’t think there’s sort of one hegemonic America hospitality model other than almost the big box, fast food Hamptons Inn on the side of the road. I’ve been working for the last two months in LA, as someone who spends most of his time in New York, I see more originality out here, but I don’t know it’s just more foreign to me because I don’t live here full time. People would probably say the most famous iconic American hospitality innovation is the roadside motel, something that I want to think about being involved in and reinterpreting.

What kind of projects do you have lined up next?

We are working on a hotel project in Baltimore right now that’s in design, so we’re hoping to begin construction later this year it was built as ‘gentleman’s bachelor apartments’ around the turn of the century, and so our design and narrative sort of harkens back to that when these wealthy bachelors would have their breakfast sent up to them in a dumbwaiter or something. That’s kind of where we’re seeing design inspiration.

[Hotel Peter & Paul, courtesy of the hotel]

[Hotel Peter & Paul, courtesy of the hotel]

[The Siren Hotel, photo courtesy of Christian Harder]

[Hotel Peter & Paul, courtesy of the hotel]

[Hotel Peter & Paul, courtesy of the hotel]

[Ari Heckman, photo courtesy of Christian Harder]

Share this Story

More Culture

Burberry Checks Into The Newt

The fashion-hospitality affair continues in the English countryside

tell me more ›Il Pellicano’s Enduring Allure

60 years of cliffside luxury, timeless style, and a spirit you can’t quite put into words

tell me more ›Bulgari Hotels Screens “An Emperor’s Jewel – The Making of The Bvlgari Hotel Roma” in NYC

Hoteliers, artists, designers, and media came together for a special screening of "An Emperor’s Jewel – The Making of The Bvlgari Hotel Roma” at the exquisite Morgan Library in New York City

tell me more ›“Becoming Familiar” Is The Experience To See and Touch at Design Miami 2023

LA Based Raise the Moral Studio Sensory Art Objects Win Best Curio Presentation at Design Miami 2023

tell me more ›